Some big offshore wind projects have recently run into the challenges of rising interest rates and delays in getting key components, and developers say some projects no longer make financial sense.

It’s a messy situation, and it threatens to undermine the future of offshore wind as a major and affordable source of electricity for the clean energy transition.

But don’t panic just yet. Rather than saying that projects can’t happen, companies are saying they need to renegotiate agreements. The result is likely to be delays and an increase in costs for consumers, which is not ideal—but far from a catastrophe.

“If governments want to ramp up offshore wind capacity fast enough to meet their longer term offshore installation goals and longer term climate goals, then they’re going to have to be happy to pay higher prices when the costs of delivering these projects increase,” said Oliver Metcalfe, head of wind energy research for BloombergNEF.

Some specifics:

- Orsted, the global leader in offshore wind, said late last month that it may write off more than $2 billion in costs tied to three U.S.-based projects that have not begun construction. The Denmark-based company said it may withdraw from the three projects (Ocean Wind 2 off of New Jersey, Revolution Wind off of Connecticut and Rhode Island, and Sunrise Wind off of New York) if it can’t find a way to make them work financially.

- The U.S. government held an auction last month for offshore wind leases in the Gulf of Mexico and attracted almost no interest from developers. One company, RWE of Germany, made a bid for one of three lease areas and won due to a lack of competition. No companies bid on the other two lease areas. Analysts said companies were reluctant to bid because the states on the Gulf do not have requirements to buy offshore wind, which reduces the opportunity for companies to sell electricity from projects there.

- Vattenfall of Sweden, another leading offshore wind developer, in July stopped work on its Norfolk Boreas wind farm off of the United Kingdom, citing rising costs. The company said this month that it is considering all options in the U.K. market, which presumably would include selling the projects to another developer, but Vattenfall is not providing much detail on its process.

- The U.K. government held an auction this month for new offshore wind project contracts and received zero bids from companies. The lack of bids was because the contracts were to pay an amount that wind developers say is too low considering the challenges of high interest rates and the rising costs of some parts.

Mads Nipper, Orsted’s CEO, outlined his company’s reasoning in an Aug. 30 call with analysts.

“Let me be clear that we will continue to carefully assess all of our options related to our awarded U.S. projects to ensure that we make the most financially responsible decisions,” he said. “As we’ve communicated earlier, we are willing to walk away from projects if we do not see value creation that meets our criteria.”

The three Orsted projects are suffering from bad timing, with leases and financial terms that were agreed upon shortly before U.S. interest rates began to rise to levels that severely cut into the projects’ anticipated profitability.

Orsted also is dealing with problems obtaining supplies, including delays from its supplier that makes the tower foundations that get installed on the seafloor.

The company is pursuing a variety of options with the federal government and state governments; state regulators or legislators could take action to change the agreements, which could include increasing the amount that utilities would pay for electricity from the projects.

On the federal side, Orsted wants to qualify for as high of a tax credit as possible under the Inflation Reduction Act. The law provides a 30 percent investment tax credit, and also has the potential for additional credits of up to 10 percent each if a project’s components qualify as “domestic content” or if the project is located in an energy community. (An energy community includes places with a history of employment in fossil fuel industries, including places with shuttered coal mines or coal-fired power plants, among other factors.)

Orsted has said it is confident that Revolution Wind will qualify as being in an energy community, but other than that is waiting for guidance from the government on the level of credits.

If states modify their agreements in response to Orsted’s concerns, consumers likely would end up paying more on their utility bills. For perspective, the current agreement between New Jersey and Orsted for Ocean Wind 2 leads to a projected monthly cost of $1.28 for a household, which wouldn’t begin until the wind farm begins generating electricity near the end of this decade.

The costs of offshore wind have plummeted in recent years, but they are still higher than onshore wind, utility-scale solar and the most efficient natural gas power plants. The hope of governments and developers is that the growth of the industry will lead to a long-term decrease in costs.

States have plenty of reasons to negotiate with Orsted rather than see the company walk away from the projects. Several states, including New Jersey, have laws with development targets for offshore wind and timelines for meeting them. And, the states are competing with each other to attract onshore jobs to support the industry.

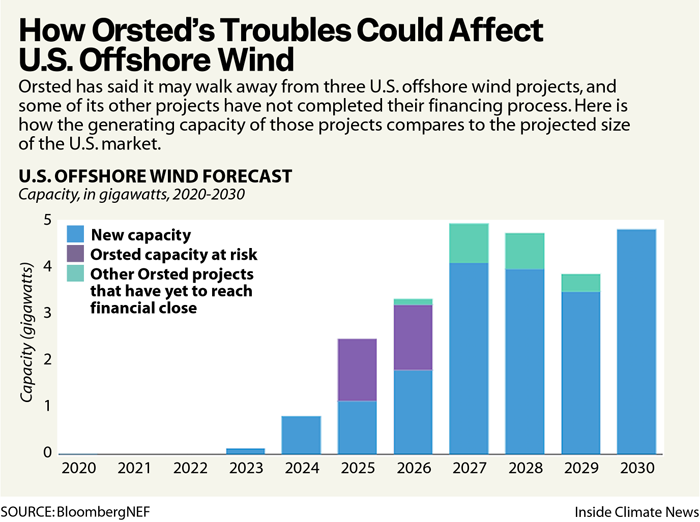

The three Orsted projects in jeopardy have a total capacity of 2.7 gigawatts. This is a little more than one-tenth of the 23 gigawatts of U.S. offshore wind capacity that BloombergNEF has previously said is on track to be online by 2030.

If Orsted walks away from the projects, the company would still hold the leases. It’s not clear what would happen next.

In the near term, the U.S. offshore wind industry will soon be celebrating completion of Vineyard Wind 1 off of Massachusetts. The 806-megawatt project is the first large offshore wind farm in the country, joining smaller projects off of Rhode Island and Virginia. (I’ve previously described it as an 800-megawatt project, but the developer now lists the higher number.)

On Tuesday, the developer announced that wind turbine installation has begun in the waters about 30 miles south of Cape Cod, with barges carrying gigantic parts out to sea for assembly.

The project should be operational sometime next year.

Keep Environmental Journalism Alive

ICN provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going.

Donate NowWhile the completion of Vineyard Wind 1 is a big step forward for U.S. offshore wind, it’s happening several years later than the developers would have liked, largely because of a long wait for environmental permits under the Trump administration.

The delays affected more than just Vineyard Wind 1, as developers of other projects waited for their own approvals, several of which have come through under the Biden administration.

The period of waiting for permits has now turned into a time of worrying about rising costs.

Metcalfe of BloombergNEF sees a glass half full in some of the recent challenges. For example, the lack of bidders for the U.K. auction shows that developers are being realistic about what they need and not signing up for contracts with unworkable terms, he said.

“If you’re the U.K. government and you want to incentivize more offshore wind, then the single quickest way to do that is to raise the price cap in the auction next year to a level that is attractive for offshore wind developers in this high-cost environment,” he said.

The actions by Orsted and Vattenfall also show some discipline, in my view, by making sure that their projects will generate enough income. In the long run, this may signal that developers are building a financially sustainable industry, which is good for the environment and the economy.

But the timing, especially in the United States, is not good, considering that the industry has barely gotten started.

Other stories about the energy transition to take note of this week:

The Inflation Reduction Act Is Reshaping Private Investment in the United States: In the year since the Inflation Reduction Act passed, spending on clean energy technologies accounted for 4 percent of the country’s investment in structures, equipment and durable goods, which is more than double the share from four years ago, as Jim Tankersley reports for The New York Times. The figures come from the Clean Investment Monitor, a new initiative from the Rhodium Group, a research firm, and the MIT Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research. Much of the investment has been in manufacturing, which holds the promise of jobs along with benefits for the environment.

Tesla Launches the Powerwall 3 Battery: Tesla has released details on its new Powerwall 3 energy storage system, a move that comes after reports that the new generation of the battery system is available for installation. Powerwall 3 has the same energy capacity as Powerwall 2, 13.5 kilowatt-hours, but it has a number of other features, including updates that allow for a more efficient pairing with rooftop solar, as Fred Lambert reports for Electrek. The previous generation model has a starting price of $8,700 before government incentives; Tesla has not published pricing on the new model.

Electric Cars Have a Road Trip Problem, Even for the Secretary of Energy: A road trip by Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm shows some of the promise and challenges of electric vehicles, according to Camila Domonoske of NPR. On the road trip, Granholm found that some places didn’t have enough chargers, or chargers that were broken, creating problems for her and her entourage and for the people who live in the areas she was touring. “Clearly, we need more high-speed chargers, particularly in the South,” Granholm said at the end of her trip.

The Southeast Is a Powerhouse of EV Manufacturing, but Utility Investment Lags the Rest of the Nation: A report from the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy helps to illustrate some of the reasons for a lack of EV infrastructure in the Southeast. The region is emerging as a leader in EV manufacturing at the same time that its utilities are lagging peers in other regions in investments in EV infrastructure. This shows a disconnect as the region has a vested interest in the success of local EV manufacturers, as Robert Walton reports for Utility Dive.

Why Native American Tribes Struggle to Tap Billions in Clean Energy Incentives: Native American tribes cannot access some of the major incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act unless they can secure an agreement to connect potential clean energy projects to the regional grid. But getting grid connections is expensive and takes years, and requires technical expertise that many tribes lack, as Valerie Volcovici reports for Reuters. The Standing Rock Sioux in North Dakota and South Dakota are among the tribes that would like to build clean energy projects—in this case a wind farm—and are running into various obstacles.

Inside Clean Energy is ICN’s weekly bulletin of news and analysis about the energy transition. Send news tips and questions to [email protected].